The summer solstice falls on 21 June, bringing the longest day and shortest night of the year.

It marks the point on Earth’s orbit around the Sun where the tilt of our planet leans the northern hemisphere towards our star, providing more heat and light and marking the start of astronomical summer.

Despite these shorter nights, there are many wonderful sights to look out for this month.

Noctilucent clouds

Our planet’s tilt is responsible for the lighter nights we experience at this time of year. This is because the Sun does not set as far below the horizon during the summer months.

This gives rise to a rare and beautiful phenomenon called noctilucent or ‘night shining’ clouds (NLCs). These appear when tiny ice crystals that form around 80km (50 miles) up in our atmosphere - higher than any other cloud – are under-lit by the Sun as it passes just below the northern horizon throughout the summer nights.

These ice crystals are believed to be at a temperature of around -130 degrees centigrade and are only visible at certain latitudes (50 – 70 degrees from the equator), only appearing in the northern hemisphere between May and August each year.

While many night sky phenomena such as the aurora and meteor showers have been observed and recorded for thousands of years, the first record of NLCs appears only to have been in 1885.

Scientists believe this may have been linked to the massive volcanic eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, which changed the abundance of certain gases and dust in our atmosphere, making water-ice more likely to form at higher altitudes.

It is also believed that dust and metallic particles from small meteors that are continuously entering and burning up in our upper atmosphere, contribute to the formation of these clouds.

How to spot noctilucent clouds

Where to look

The formation of the ice crystals occurs high in the atmosphere in the colder air above Earth’s poles, so look north. This will likely be the lightest part of the night sky at this time of year as the Sun lies just below the northern horizon.

When to look

The angle of the Sun’s light is most likely to illuminate ice-crystals forming in our upper atmosphere around an hour or two after sunset and before sunrise.

What to look for

While normal clouds appear darker against the night sky, noctilucent clouds seem to glow with a blue-ish tint. This can be very pale, but brighter displays can appear a stunning electric blue. The blue-ish glow can be key to identifying NLCs from towns and cities, where our light pollution tends to under-light normal clouds with a yellow-orange glow.

While normal clouds will dim or block the light of the stars beyond, the finer structure of NLCs very often allow the light of stars through.

Another way of identifying NLCs is through their structure. While normal clouds have the classic ‘fluffy’ appearance, NLCs tend to appear more finely structured, with distinct and often straight lines or even grid-like patterns within them.

The Moon and planets

Venus is the highlight of our evening skies over the coming weeks. The planet becomes visible soon after the Sun sets in the west and gets steadily brighter as the skies darken.

Venus is currently around 100 million kilometres (60 million miles) away from us, and shines brightly because of its reflective atmosphere; a thick, toxic mixture of carbon dioxide and sulphuric acid that reflects the Sun’s light.

Did you know?

Venus spins so slowly on its axis that one day on the planet lasts around 243 Earth days. That’s actually longer than it takes for Venus to orbit the sun (225 Earth days), meaning a Venusian day is actually longer than a Venusian year!

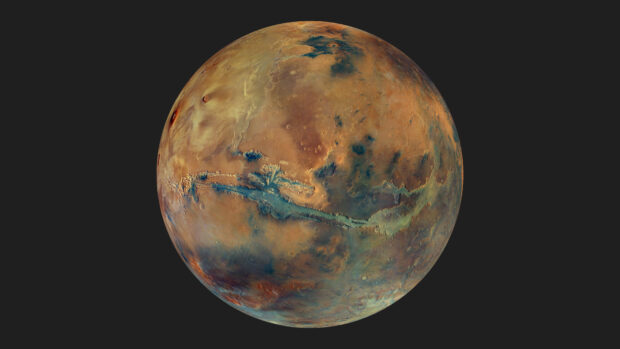

Mars currently lies a short distance up and left from Venus, as the two pass through the constellation of Cancer (the Crab) this month heading towards Leo, which we featured in last month’s blog.

Our two planetary neighbours are joined by a waxing 15% illuminated Moon on the evenings of 21 – 22 June.

As Venus and Mars set in the north-west at around midnight, Saturn begins to rise in the south-east, followed a couple of hours later by Jupiter.

Early risers can spot Saturn next to a 60% illuminated Moon on the morning of 10 June, while Jupiter appears to have a very close encounter with the waning, 15% illuminated moon on the morning of 14 June.

Leave a comment