On Tuesday 4 May, the UK’s Space Operations Centre (UKSpOC) based at High Wycombe started monitoring the re-entry of an object into the Earth's atmosphere.

The object, measuring approximately 33 meters long by 5 meters wide and weighing approximately 18 tonnes, was debris from a spent rocket: CZ-5B (translated as Long March-5B), which started to return to Earth after carrying a module for Tiangong, China’s next space station.

Rocket launches are usually made up of two or three stages and the components come in varying sizes – with the Chinese Long March-5B rocket being one of the biggest.

Usually, the large booster rockets fall back to Earth, typically in the ocean, or burn up as they re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. The exceptions to this are reusable booster stages, like those developed by SpaceX, which are refurbished for their next flight.

This event was of particular interest because Long March is claimed to be the biggest object to return to Earth since the 1990s, matched only by the re-entry of the previous Long March-5B rocket that re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere in May 2020. Pieces of debris assumed to be from this rocket were subsequently identified on the ground in Cote D’Ivoire in West Africa.

How does the UK track objects in space?

The UK Space Agency and the Ministry of Defence closely monitor a range of activities in space, including satellites, space debris and returning rocket launchers, through our joint Space Surveillance and Tracking (SST) capabilities.

SST uses sensors, usually radars, telescopes, and laser-ranging systems, to provide tracking data to reduce orbital hazards. The most dangerous events we track are collisions in space between objects, but we also monitor and predict atmospheric re-entries of objects like this rocket body. In most re-entries nothing of the object survives to reach the ground as it burns up harmlessly in the atmosphere.

For this event however we knew that some debris was likely to survive due to the size of the rocket body.

Re-entry locations and timing are typically difficult to predict as characteristics of the satellite, such as its attitude (the direction it's pointing in), size and mass along with a changeable atmospheric density can have large impacts on the accuracy of analysis.

A good description of these factors can be found in this blog from the European Space Agency. These uncertainties regularly result in the predicted re-entry time and location changing in the days and hours before an object finally enters the atmosphere.

The UK Space Agency's Orbital Analysts, who work for a Northumberland-based company called NORSS (Northern Space and Security), work alongside the UK SpOC’s Military Orbital Analysts and jointly analysed the Long March-5B trajectory using information provided by the US Space Surveillance Network which includes data from RAF Fylingdales.

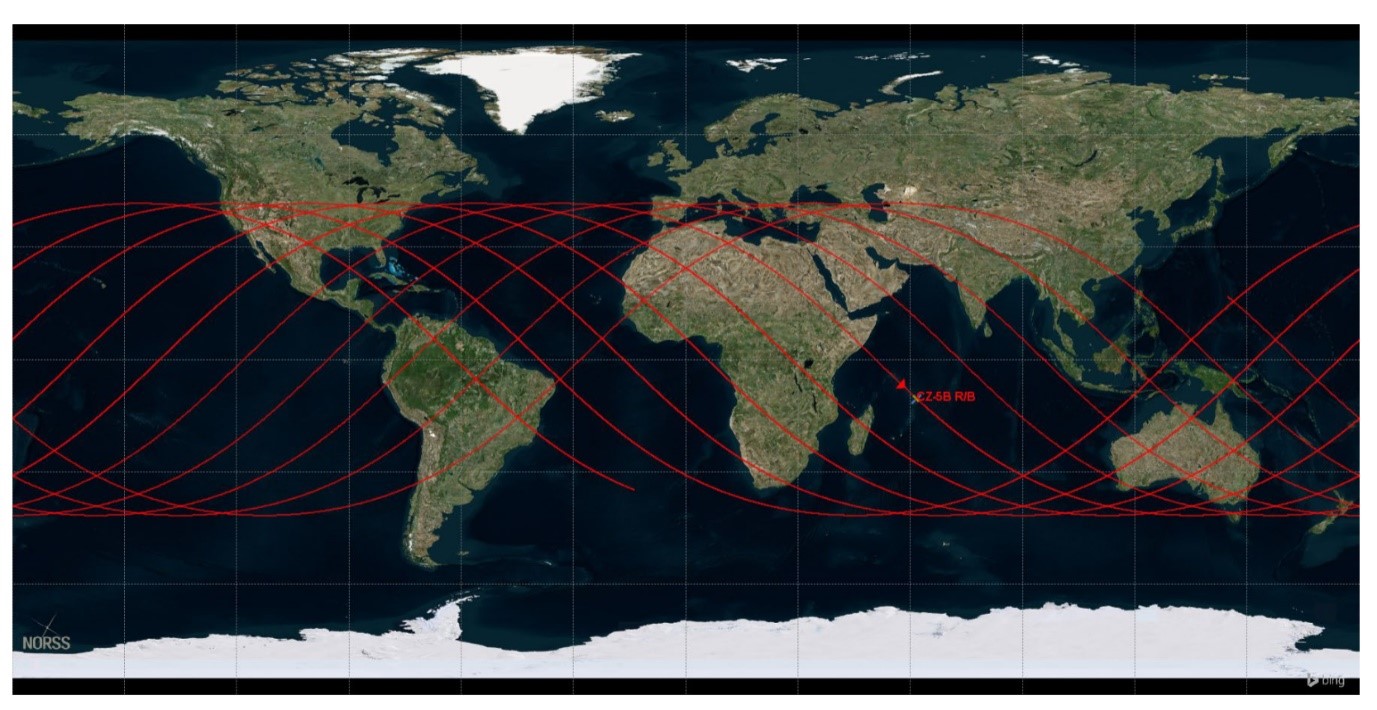

The orbital analysts ran this data through their models to produce multiple possible re-entry points, which are shown in the red lines in the images below.

The first image shows the re-entry calculations predicted on 6 May, three days before the event, mapped on a simple image of the Earth.

Due to where the rocket was launched from, and the orbit it was now in, we could be confident it would fall within a certain distance of the equator and not re-enter too far south or north. At this stage we were certain there was little risk to the UK, but we kept tracking it anyway, just in case. We also shared our predictions and data with other space agencies.

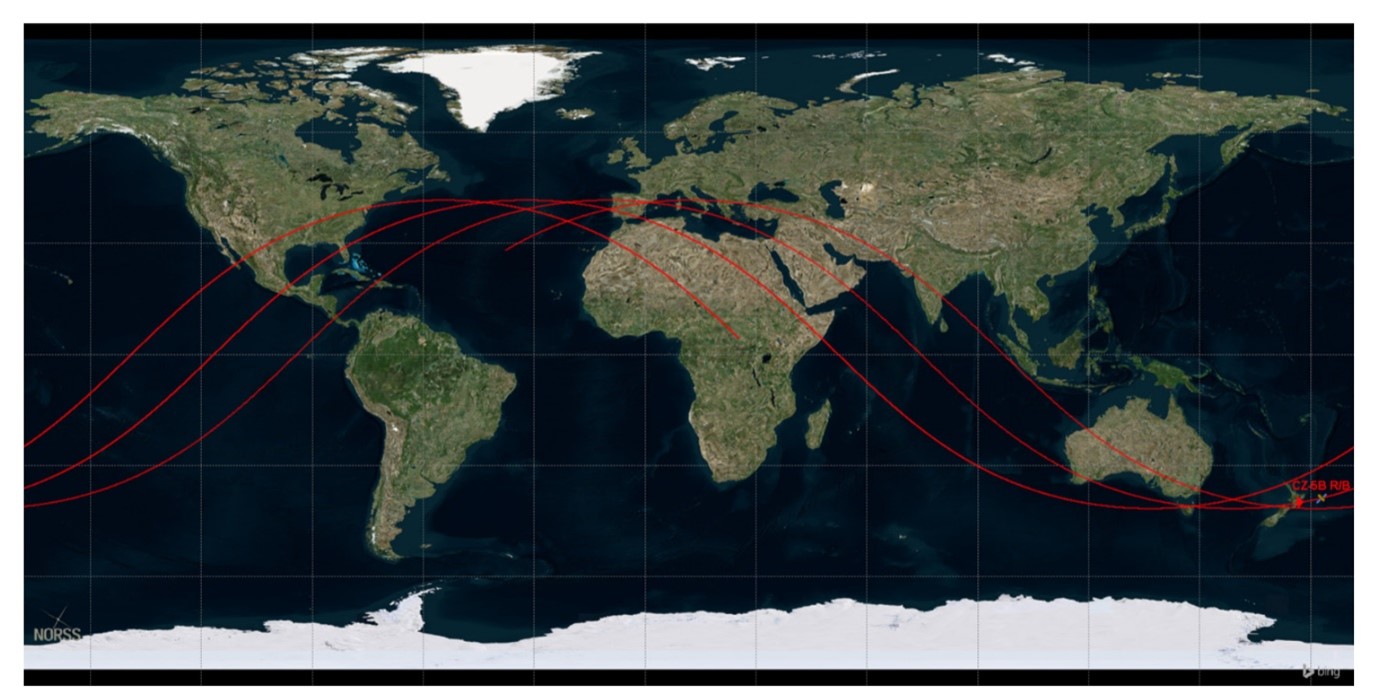

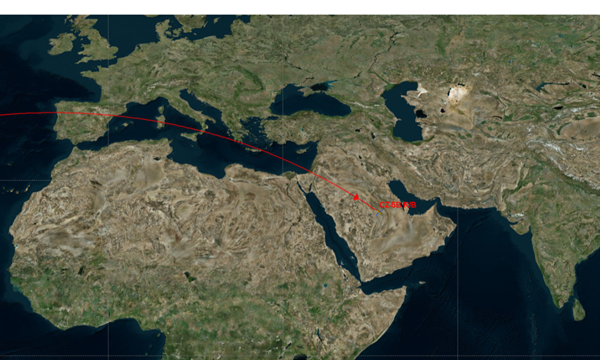

The second image shows the re-entry predictions from one day before the event, and the third image shows the actual re-entry point.

As you can see, the options get narrowed down as more information about the re-entry becomes available. The maps below also show that the actual re-entry of Long March-5B matched one of the four possible re-entry tracks we predicted one day before the event.

Though you can’t see it on the map, the time of re-entry is also important to where the event might occur, and in this case the predicted re-entry time from our last calculation was within minutes of the actual re-entry time.

On Sunday May 9, as the third image shows, the rocket re-entered the atmosphere above the Arabian Peninsula and any remaining fragments likely landed in the Indian Ocean near the Maldives.

Why it matters

Public agencies use this type of analysis to warn national operators and government authorities of unexpected events or the risk to infrastructure and life from atmospheric re-entries, although it is the responsibility of all nations to ensure that activities in space are conducted safely.

This event highlights the problem of debris in space and its potentially wide-ranging considerations. This is a growing issue with approximately 160 million objects in orbit – mostly debris created by humans, such as spent satellites, paint flecks, machinery, and rocket bodies.

With the estimated launch of 45,000 new satellites into low Earth orbit over the next few years, this space debris problem will mean our ability to track objects in space becomes increasingly important to avoid any satellite collisions, or to predict where objects already in orbit might re-enter. Our biggest concern remains the growing congestion and debris in orbit.

Our growing need to protect and defend our interests in space is why the UK Space Agency and the Ministry of Defence have worked together since 2015 to monitor orbital events.

Our analysts work jointly with MoD seven days a week, 365 days a year to monitor and track the safety of UK satellites. The UK is the largest contributor to the European Space Agency’s space safety programme, which we use to develop new sensors and tools to support our predictions.

We are also enhancing a joint civilian and military National Space Operations Centre (NSpOC) that will continue to provide Command and Control of Space assets and develop space domain awareness to keep the Government and UK industry informed.

Leave a comment