Advanced infrared technology offers a new lens through which to probe the unknowns of the Solar System.

Infrared (IR) instruments are a powerful tool for space exploration because they can investigate the composition and properties of gases, liquids, and solids to high precision.

Infrared (IR) light is emitted by any object based on its temperature. Like red light has a longer wavelength than blue, infrared is a ‘colour’ with longer wavelength that steps past red and into parts of the rainbow that are invisible to our eyes.

What IR light can reveal about thermal properties can be useful in characterising an object: pit viper snakes use IR to hunt via the body heat of unsuspecting rodents, thermal cameras pick up IR to check insulation in homes, and IR instruments in orbit study Earth’s climate.

There is a plethora of uses for IR in space.

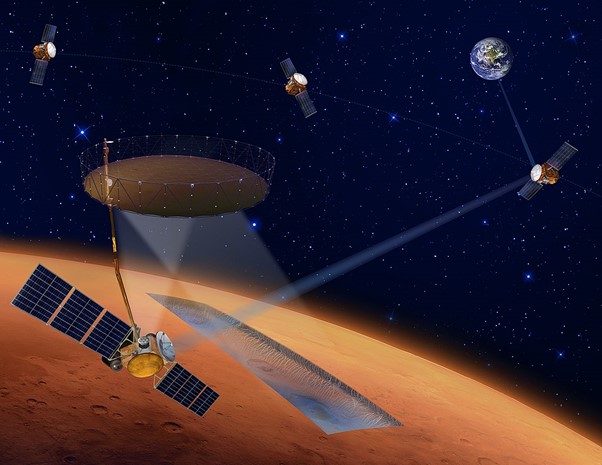

In the exploration of Mars, IR cameras can map the surface composition and unveil hidden aspects of the planet. Infrared light is key for reconnaissance of zones for humans and rovers before we set foot on the surface.

For example, IR can identify vital in-situ resources like water. On Mars, water is not easily accessible and exists primarily in the form of ice or bound within minerals, making it difficult to locate and use.

There is a need for high-performance IR detectors to, among other things, identify and analyse resources, but traditional methods of detection fall short in terms of precision and reliability in extreme environments.

A team at the Open University have taken on this challenge in a project led by Professor Manish Patel, in collaboration with Teledyne e2v, and supported by the UK Space Agency.

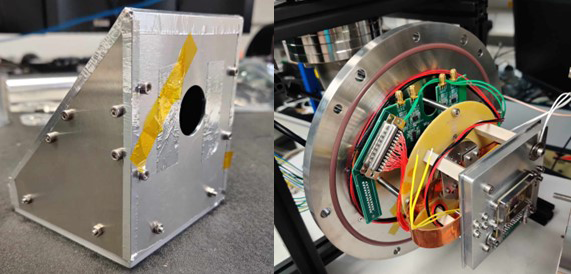

With a name that highlights the difficulty of space engineering, the ‘NITEMARES’ project (Novel Infrared Technology for Exploring Mars, Advanced Reconnaissance And Exploration Science) is built on previous UK Space Agency-supported studies to develop IR technology to operate more reliably in the hostile space environment.

The focus of NITEMARES was to improve technology maturity for future space missions by testing the performance in conditions like those seen in orbit around Mars.

In particular, the project contributes technology to imaging of near-surface water ice in mid-to-low latitudes to support planning for the first potential human surface missions to Mars.

This presented several engineering challenges, including creating a novel set up to cool the device to stable low temperatures, minimise background IR radiation, and irradiate the device with protons to mimic space radiation.

The project went on to produce a roadmap that set out the pathway for a space-qualified detector suitable for a Mars mission in the 2030s.

The Open University’s successes strengthen the UK’s position of leadership in IR technologies and highlights the UK as a preferred partner on future collaborations.

Building on the achievements of this project, a consortium led by the team at The Open University was awarded a further £2 million to build IR technology for the International Mars Ice Mapper (I-MIM) being developed by NASA and the Japanese, Canadian, and Italian Space Agencies.

NITEMARES lays the groundwork for future opportunities in space exploration and has potential exciting spinouts for wider space-based imaging, defence, and commercial applications.

Leave a comment