The international space community has its sights on Mars, with government agencies and commercial businesses alike aiming for boots on the red planet. This is enabled by technological innovation, which is pushing the frontier of space out of the Earth-Moon neighbourhood and into the wider Solar System.

To boost UK capability and play a leading role in this effort, the UK Space Agency is funding propulsion technologies capable of supporting long-duration and deep-space missions.

In general, travelling through space involves throwing things away from a spacecraft so it accelerates in the opposite direction, like shooting a fire extinguisher off the back of a skateboard. Chemical propulsion works by burning fuel and accelerating the exhaust through a nozzle to push the spacecraft onwards.

This is a tried-and-tested method but has some drawbacks. Fuel is heavy and the spacecraft must hold all the chemical propellant it needs for its lifetime. To launch heavier spacecraft is expensive and requires even more fuel to get off the launch pad.

For longer missions into deeper space, more propellant is needed, and traditional chemical propulsion becomes less feasible.

An alternative is electric propulsion, which works by shooting out charged particles at enormous speeds around 100 kilometres per second. Though lower in thrust, it is more efficient and does not require carrying huge amounts of fuel.

This makes it a favourable candidate for longer missions, but a key barrier for electric propulsion is the substantial power requirement.

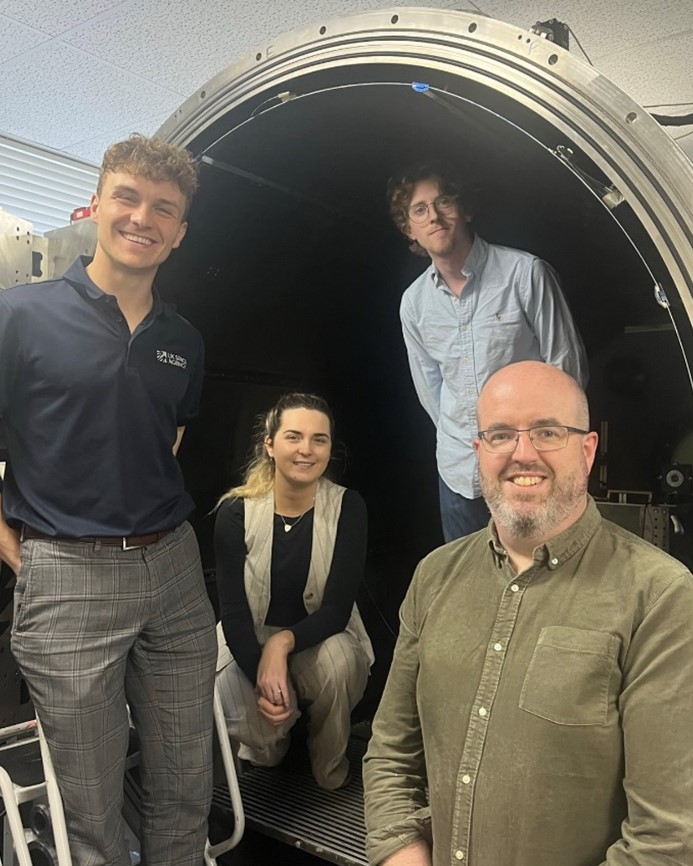

To overcome the obstacle of power, the UK Space Agency awarded an ‘Enabling Space Exploration’ grant to integrate nuclear power with electric propulsion. This development of Nuclear Electric Propulsion (NEP) technology was led by the University of Southampton with partners including the University of Cambridge, PULSAR Fusion, and the National Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (NAMRC).

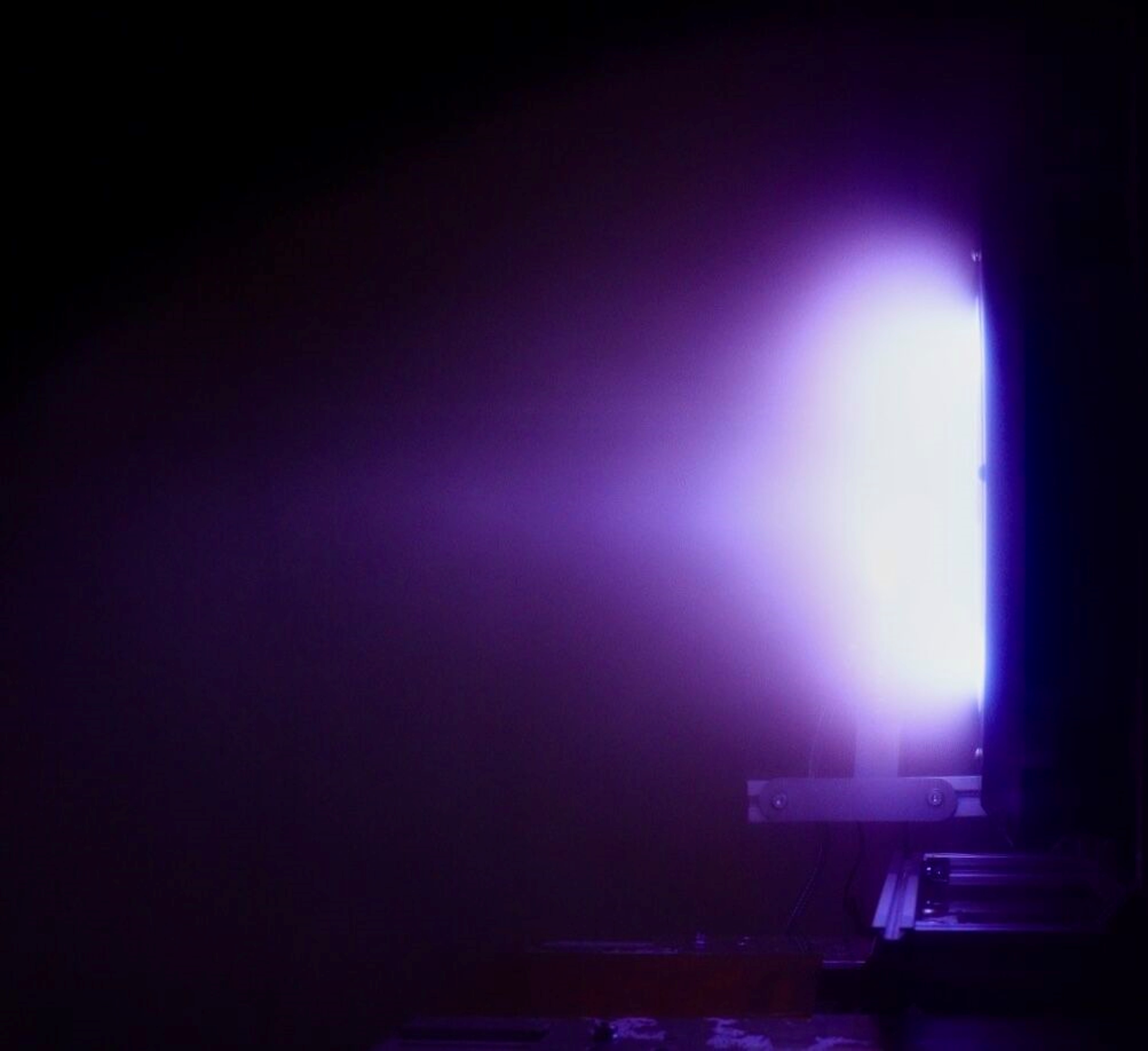

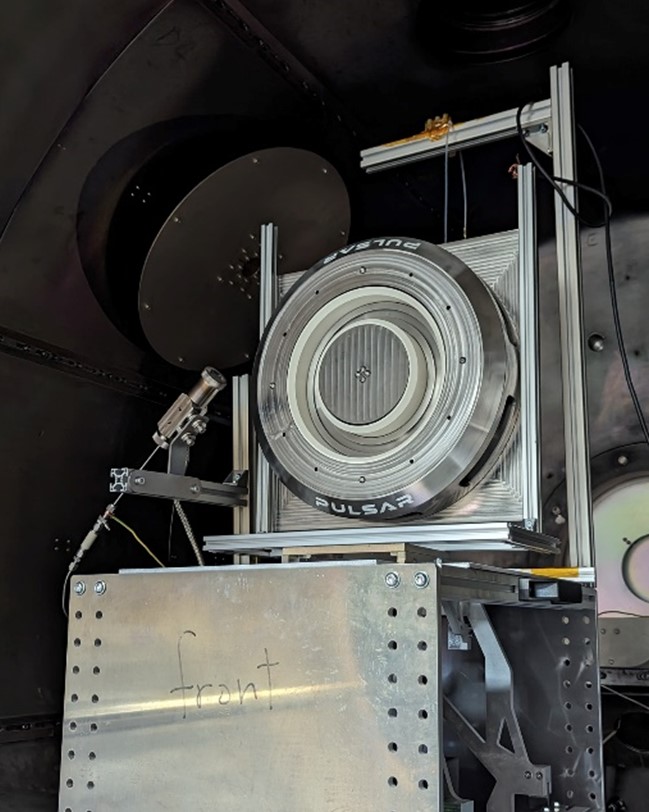

A notable achievement of this project was the development and testing of a type of electric propulsion, called a Hall ion thruster, which was designed in-house to be compatible with the newly developed nuclear reactor. The resulting Hall thruster is potentially the largest in Europe, with a power output thought to be 10kW, though it was too powerful to fully verify in any of the UK’s vacuum chambers.

To better understand the requirements of the system, this project identified missions where it would be advantageous to use NEP. Several mission-types were found to benefit, such as crewed or cargo missions to Mars. This would take advantage of faster transit times to Mars, allowing a 2-year return trip.

Another possible use for NEP is advanced exploration missions to the outer Solar System. In these depths of space, solar power is too low and improved manoeuvrability of NEP would allow for insertion into orbit around other bodies, for example Pluto.

NEP technology may form a cornerstone for future space missions planned by agencies such as the UK Space Agency, European Space Agency, and NASA.

The completion of this project not only underscores the UK's leadership in advanced space technology but also aligns with global efforts to explore deeper into the Solar System. Through this project, the UK has reinforced its strategic capabilities in the space sector, promoting technological innovation and enhancing the potential for future exploration and discovery.

Leave a comment