With the planets lining up in our early morning skies, the return of the core of our Milky Way Galaxy, and the Lyrids meteor shower towards the end of the month, April can be a great time to enjoy the stars as the nights start to warm up a little.

A recent night under the dark skies of the Brecon Beacons (with the temperature steady at a biting -4°C!) reminded me we may not be quite there yet, so remember your coat, gloves and hat, and enjoy the spring night skies!

Spring Constellations

Between the large spring constellations of Ursa Major and Leo lie the less well-known but fascinating constellations of Canes Venatici and Coma Berenices.

Little can be seen in these constellations from larger towns and cities, but escape from the light pollution to a dark-sky site and this area of sky takes on a wonderful ghostly glow. The cause of this is revealed by the nickname for this patch of sky: ‘The Realm of the Galaxies’.

Our galaxy is the shape of a flat disc. Although scientists believe it to be over 100,000 light years across, it’s likely only around 1,000 light years ‘thick’ - think giant cosmic dinner plate!

When we look into the plane of the disc, we’re looking through space occupied by hundreds of billions of stars, swept into the disc’s shape by gravity and the rotation of our galaxy. This concentration of stars appears to us as the ‘Milky Way’, a bright, narrow strip of stars visible across our night sky.

When looking up at Coma Berenices, we’re looking almost directly up and out through the ‘thinner’, much less occupied region of space, where the edge of our galaxy is much closer.

As a result, there are fewer stars, and fewer clouds of cosmic gas and dust to obstruct the view of our universe, making distant galaxies easier to see.

While you’ll need a telescope to make out the individual galaxies (weather permitting, we hope to have a photo next month), the glow from the distant light of billions of stars in countless, far away galaxies can be seen with the naked eye – a wonderful sight, but you’ll need to get as far away from ground light as you can to see it.

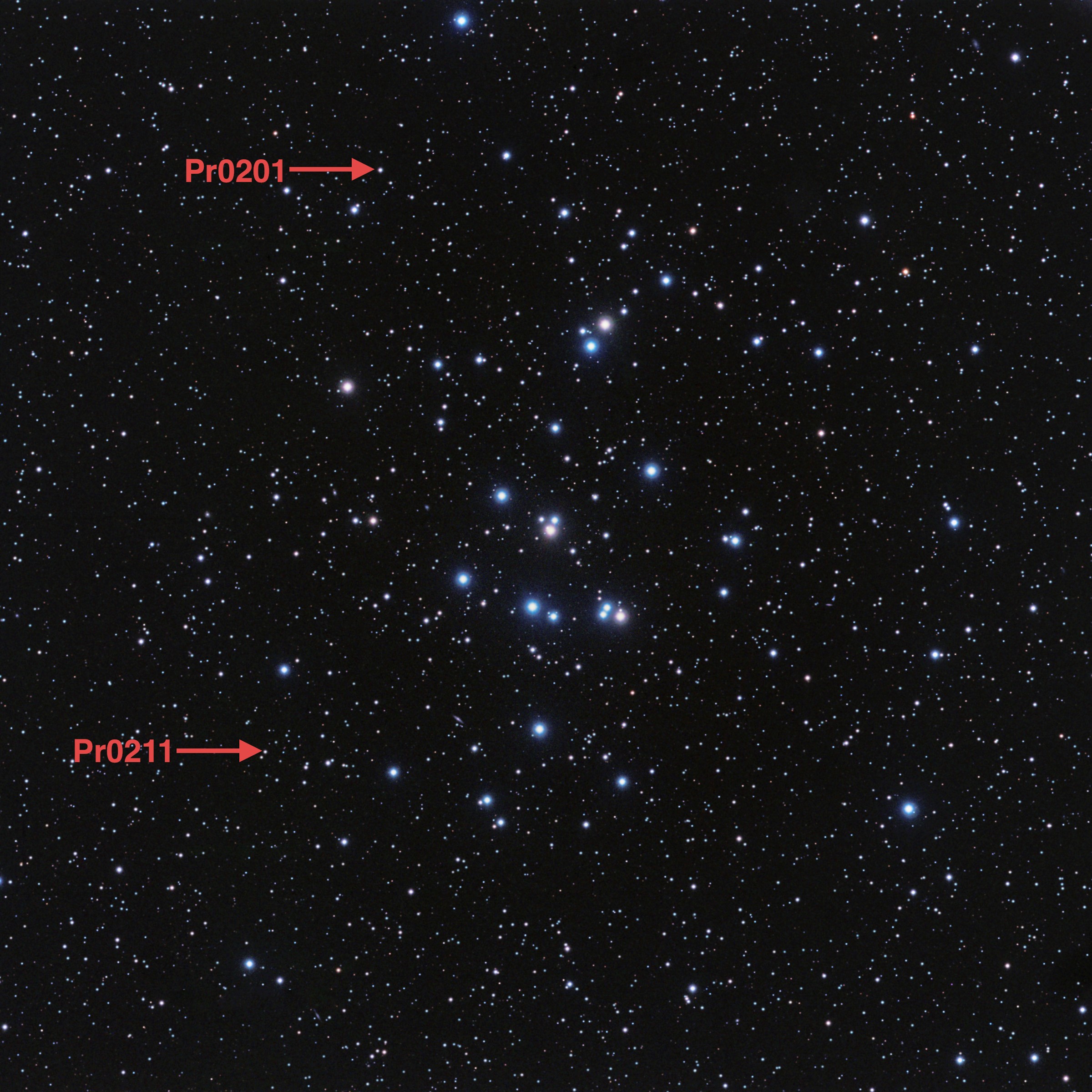

Much closer to Earth, the small constellation of Cancer (the Crab) can be seen, seemingly chased by Leo across the sky. Cancer hosts one of the closest open star clusters to Earth, a swarm of around 1,000 stars, travelling together around our galaxy, currently around 500 – 600 light years away from our Solar System.

In 2012, the Kepler spacecraft that was designed to hunt for planets around stars other than our own (so called ‘exo-planets’) found two ‘hot Jupiters’ within the Beehive cluster – large gas giant planets similar to Jupiter, except that they orbit very close to their parent star.

The Moon and Planets

The planets continue their dance in the early morning skies.

Rising in the east just after 5am, Mars and Saturn appear to almost touch in the first week of the month, with brightest planet Venus just a short distance away.

Jupiter joins them an hour of so later, but will quickly fade into the light as Sunrise approaches.

By the last week of the month however, Jupiter will be visible earlier and will appear to move closer to Venus. So close in fact that they’ll appear to merge into a large glowing point of light on the last morning of the month.

In reality they’ll be more than 600 million kilometres (370 million miles) apart, but you’ll need powerful binoculars or a small telescope to separate them from our perspective here on Earth!

Towards the end of the month, the waning Moon passes just underneath these four planets, a helpful guide if you’re not sure where to look.

Mercury will join them next month, but for now, the closest planet to the Sun can be seen in our evening skies.

Particularly prominent towards the end of the month, look for the bright point of light just below the Pleiades (or Seven Sisters) star cluster, low in the west after the Sun sets.

The Lyrid Meteor Shower

This month sees our planet pass through the material left in the wake of C/1861 G1 Thatcher, a comet that passes through the inner solar system every 415 years. The peak of the resulting meteor shower is expected to take place on 22 - 23 April, but meteors could be visible for a week or so either side of this.

Chinese astronomers recorded sightings of the Lyrid meteors as far back as 687BC, but the infrequent passage of the comet causing them meant it wasn’t discovered until 1861. We’ll not see Comet Thatcher again in our lifetimes, with its next passage around the Sun expected around 2283!

These meteors are caused by the cometary debris hitting our atmosphere, travelling at great speeds of around 50km (30miles) per second. For the best chance to see them, try to get away from sources of ground-light and face away from the Moon, which will be low in the southern sky. Good luck!

The International Space Station

This month the orbit of the International Space Station means there aren’t any opportunities to catch it passing over the UK.

It returns to UK skies in May, however, and as the nights get shorter with the Sun sitting just below the horizon at night over the coming months, there’ll be more bright passes to look out for!

Join us next month to find out about May’s total lunar eclipse, the Eta Aquarids meteor shower and more planetary conjunctions.

Until then, wishing you clear skies!

Leave a comment