On 15 November 2021, the UK’s Space Operations Centre (UKSpOC) based at High Wycombe started monitoring the fragmentation of COSMOS1408 – an inactive, two tonne Russian satellite which had been struck by a Russian anti-satellite (ASAT) missile test.

Fragmentation events are the break-up or explosion of objects in space. This can happen for a number of reasons, including satellites colliding with debris or with other satellites, through a fuel tank exploding, or by deliberate missile tests like this one.

Data suggests this event generated more than 1500 pieces of trackable debris in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) at an altitude of 450-500km; increasing the risk of debris colliding with satellites in LEO.

The UK Space Agency maintains a team of Orbital Analysts who monitor orbital hazards and risks to the UK from satellite collisions, fragmentations and re-entry events 365 days a year.

The UK Space Agency’s analysts were alerted to the fragmentation incident by their military colleagues in the UKSpOC early in the morning of 15 November and quickly started analysing the consequences of the event.

How does the UK track objects in space?

The UK Space Agency and the Ministry of Defence closely monitor a range of activities in space, including satellites, space debris and debris returning to Earth, through our joint Space Surveillance and Tracking (SST) capabilities.

SST uses sensors, usually radars, telescopes, and laser-ranging systems, to provide tracking data to reduce orbital hazards. The UK Space Agency has recently (November 2021) placed new contracts with Commercial sensor providers like Numerica giving the UK access to more data on objects in orbit and this supplements existing sensor capabilities provided by UK government-owned assets.

The UK Space Agency's Orbital Analysts, who work for a Northumberland-based company called NORSS (Northern Space and Security), work alongside the UKSpOC’s Military Orbital Analysts and analysed the fragmentation event using both simulated data and information provided by the US Space Surveillance Network - which includes data from RAF Fylingdales in North Yorkshire.

How did the UK Space Agency respond to the ASAT test?

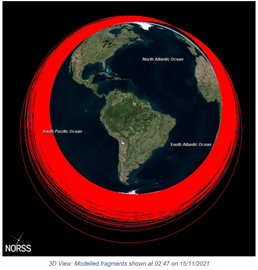

Having identified the target satellite and the time of event, UK Orbital Analysts were able to simulate the event and the debris it created, using a breakup model originally developed by NASA.

Whilst the exact position of each real fragment cannot be determined in this way, the approximate number of fragments and how high they were (their altitude distribution) can be estimated to a reasonable accuracy.

This is very helpful in understanding and calculating increased risk to satellites on-orbit by enabling us to focus on satellites which were estimated to be passing closest to some of the new debris.

Much of the public commentary during the event focussed on the risk caused to the International Space Station (ISS).

Using this break-up model, the Analysts generated a video visualisation which follows the ISS through a simulation of the debris generated during the first few hours of the ASAT fragmentation event. The simulation uses open-source data and modelling from UK Space Agency Orbital Analysts.

NB: The simulated debris shown in the above video is only that generated by the ASAT test – it does not show all of the approximately 11,000 other pieces of trackable (over 10cm) debris in this orbit already. This video also only shows the ISS – there are of course many other spacecraft operating in Low Earth Orbit – including the Chinese Space Station (also crewed) and UK-licensed satellites. All of these other spacecraft are also expected to be at risk from colliding with the debris from this event for several years.

Information and analysis generated by our Orbital Analysts were disseminated daily to cross-government incident response teams and shared with international partners.

We contacted UK-licensed satellite operators in LEO and continue to actively monitor and warn operators if their satellite is perceived to be at risk of a collision.

Why is this event important?

Over the short-term, spacecraft in the vicinity of the ASAT test have seen an increased risk to their safety – meaning they are at a higher risk of colliding with debris due to the additional fragments generated by this event.

The UK Space Agency Orbital Analyst Team carried out initial collision screening of UK licensed satellites versus the trackable debris field (i.e. using real data not simulated data). This predicted an average increased risk of over 10% for UK-licensed objects in LEO.

The majority of the newly created debris will likely remain in orbit for many years meaning this average increase in risk will persist for the majority of this time. Debris in this orbit also poses a risk to newly launching satellites, many of which have to boost through this region.

The observable fragments are a major problem but can be assessed for possible collisions, and in many cases spacecraft can take avoidance measures (such as those carried out by the ISS on 15 November).

However, the small debris that can't be tracked and could cause damage to spacecraft is also concerning.

As time goes on, the debris will spread out, some of it will re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere fairly quickly due to gravitational pull and atmospheric drag, however the majority will remain in orbit for many years.

Therefore, the debris cloud poses an increased long-term risk to all satellites and crewed spacecraft in LEO. Understanding the extent of the debris generated will take weeks and the full extent will never be understood as fragments below 10cm will not be able to be tracked and catalogued.

The space debris problem will mean our ability to track objects in space becomes increasingly important to avoid any satellite collisions, or to predict where objects already in orbit might re-enter.

Our biggest concern remains the growing congestion and debris in orbit, which this event has worsened.

UK efforts in space sustainability

This summer, during the UK-hosted summit, G7 nations committed to the safe and sustainable use of space. The UK is committed to ensuring the sustainability of space and is working alongside global allies to promote space sustainability initiatives.

Our growing need to protect and defend our interests in space is why the UK Space Agency and the Ministry of Defence have worked together since 2015 to monitor orbital events.

We are also enhancing a joint civilian and military National Space Operations Centre (NSpOC) that will continue to provide space domain awareness to keep the Government and UK industry informed. Our analysts work jointly with MoD seven days a week, 365 days a year to monitor and track the safety of UK satellites.

The UK is the largest contributor to the European Space Agency’s space safety programme, which we use to develop new sensors and tools to support our predictions.

Delegates from the UK Space Agency have also played a key role in developing and agreeing the United Nation’s Long Term Sustainability Guidelines and funded a project with the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs on raising awareness and capacity building related to the implementation of those Guidelines.

Athene Gadsby is the Space Surveillance and Tracking Operations Lead at the UK Space Agency

Leave a comment