In the early 80’s, in what seems a lifetime ago but is only half a lifetime, I returned to Imperial College from a spell in the USA.

There, I had started working on some science problems of the giant planet magnetospheres. The inspiration had been the flybys of Jupiter and Saturn by the Voyager spacecraft. At that time, there was really little or no work on this topic going on in the UK.

In one or two European nations the excitement of the Voyager images had sparked an increasing sense of frustration that Europe was taking little part in exploring the outer planets. Eventually, pressure from a few senior scientists in Germany, France and Switzerland resulted in the European Science Foundation setting up a group of European scientists to join with a similar group of Americans to look at what European-American collaborations might be possible in the field of Giant Planet science.

Right place, right time

For me it was a wonderful example of being in the right place at the right time. It was important to have a Briton in the group and who was there? They drafted me in. The ten person-group met a few times but it was rapidly clear from the first what the next grand challenge would be, an orbital tour of the Saturn system. But what else? The US planned Galileo mission would include a probe diving into the Jupiter atmosphere. Rapidly, we homed in on something substantially different. We should propose a lander on Saturn’s moon, Titan, the only moon in the solar system with an atmosphere as thick as Earth.

The scientific unknowns were easy to bring into place as Voyager had given us many questions with each surprising discovery. The difficult issue was what Europe should do and what the Americans should do. Managerially, it was important to divide things into engineering packages with as clean interfaces as possible. In the end, we proposed the Titan lander to be built in Europe. Many of our US friends were uncomfortable. Europe had no track record!

As regards science it was easier. Both Lander and Mother ship would have European and American instruments; there would be a global competition. Then came the real battle, to persuade ESA and NASA that such a mission made sense. It took six years before both agencies had taken the idea on board. It seemed a long time but in fact, in retrospect, it was incredibly quick.

The mission idea was adopted by ESA and NASA in 1989. In Europe, the science community gathered in Bruges for the public presentation of 5 competing mission studies. For me, it was magical. By the end of the day, it was clear that the Saturn Orbiter Titan probe mission was going to win!

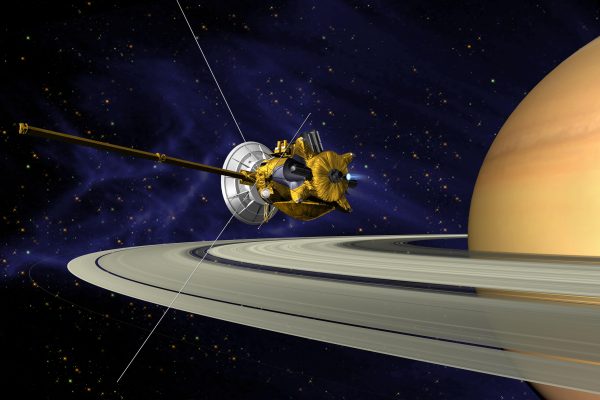

As I came home to England, I was already thinking about the competition that would come to build an instrument. A team I led proposed an instrument to build the Cassini magnetometer. We had two competitors. In 1991, we heard we had won; a British-led instrument would fly on the American Mother-ship. I became the Cassini magnetometer principal investigator (PI). A second UK instrument PI, John Zarnecki, led the surface science package on Huygens. We would be seeing a lot of each other in the years to come.

Threats to the mission

The next years flew by. Design, build and testing (over and over) of an instrument part of which was being provided by German and American collaborators and then interfacing to fly on a very large US spacecraft was a demanding job for the small Imperial College team. Moreover, even in the US the big mission planned faced a difficult ride.

For cost saving reasons, the programme was merged with a cometary/asteroid programme called CRAF (Comet Rendezvous Asteroid Flyby) also run out of Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. The cometary mission costs were spiralling driven by an asteroid penetrator and it looked like killing everything. In the end rationality prevailed. CRAF died and Cassini alone emerged from the ashes, only to face another major threat.

A change of management in NASA led to a philosophy that spacecraft were going to be “faster, better, cheaper”. Cassini was manifestly planned to be the best one could think of for going to visit the vast complex Saturn system with its giant planet, its many moons (62 at last count), its rings, its magnetosphere and so on. But could it ever be done faster? That was an unreasonable risk. Worst of all, it was never going to be cheap.

Right now, I imagine there isn’t anyone in NASA who isn’t extremely glad that it came through. However, it clearly did not fit with the tenor of the times. The European cooperation almost certainly saved it. Diplomatic efforts were mounted across Europe to prevent the US cancelling the mission. Once again, chance played into my hands. I had met Dan Goldin, the new NASA head socially when I had been in the US. I wrote directly to him, as chair of the ESA Science Programme Committee, laying out the depth and importance of the European collaboration. However, I included some personal greetings that I hoped would prevent any standard response from the office. A few months later, the NASA Science head told me she had watched her boss study the letter. How influential it was, we probably will never know, but Cassini was reprieved.

From then on the technical work became the dominant challenge. Eventually, and in retrospect, actually rather quickly for something this ambitious, in October 1997, came the launch. At a launch there are mixed feelings. Knowing your instrument is sitting on top of a lot of high explosive is stressful but there is an enormous relief in seeing it on its way. A Titan IVB night launch is very memorable. Nature assisted the spectacle by providing a cloud on the trajectory. As the rocket flew through it, the whole sky lit up.

That same month I made a big career move, going from being head of Physics at Imperial to a job in Earth Observation at European Space Agency. There were seven years of cruise ahead, I had a great second-in-command, Michele Dougherty, I arranged regular visits to Imperial and I remained the instrument PI. After a short return to Imperial in 2001, I went back to ESA to become Director of Science and so responsible for the European side of the mission. In 2004, we entered Saturn orbit. Here there was another decision. I should not continue as PI as we went into the full science phase of the mission. It seemed clear to me that Michele Dougherty should take over and she led the team brilliantly from then on. I now found myself responsible for the Huygens probe descent on to Titan. It was scheduled for January 2005 and there would be a flyby of the moon in October when we would get some data on the atmosphere we had to descend through.

Deployment of the Huygens lander

On December 25 2004, Cassini released Huygens. It would fly on its own for 3 weeks. I did not sleep much; the year before we had lost Beagle2 landing on Mars, a second failure was unthinkable. In the event, all went well. There were panics and glitches. At the same time there were magnificent surprises. As Huygens descended Cassini picked up its signals and relayed them to Earth for 1h 12m from Huygens on the surface at which point it went over Huygens horizon. The radio astronomers of the world combined their telescopes to point to Titan and to pick up Huygens tiny (mobile phone scale) signal directly for 3h 14m.

I don’t know how to describe my feelings on landing. We were looking at an entirely new world (hitherto hidden by thick cloud) and one with a pre-biotic atmosphere that contains Nitrogen, Hydrogen and Carbon. The moon itself contains Oxygen. One day, say, as the Sun becomes a red giant and Titan is warmed, would life appear? We had always said that there might be a methane driven meteorology and indeed we could see evidence of river channels that might sometimes contain methane rivers. I found the whole experience so overwhelming, I was reduced to quoting Keats in an attempt to express the enormity of the emotions that we felt:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific - and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise -

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

My NASA counterpart expressed his feelings by simply bursting into tears.

Of course, the orbiter mission itself had hardly begun. Science came in thick and fast. For me, the highpoint was the discovery of the magnetic signatures of geysers of the tiny moon, Enceladus which orbits just outside Saturn’s rings. The key discovery from came from the instrument, the magnetometer that I built. My successor as magnetometer PI, Michele Dougherty, had to convince the project that the squiggles on a plot of data picked up as the spacecraft flew over the moon meant something incredible was happening inside the moon. She was successful in persuading the project engineers that we should go back and take a closer look. They allowed it and, indeed, just as the magnetic field team had been saying, Enceladus was shooting water vapour into space. There must an interior ocean! If there were an ocean it could even harbour life.

I could go on and on elaborating the wonderful science that has come from Cassini extended visit to extraordinary Saturn system. I am not going to do this. Right now I’m still working on data from my instrument and will go on doing so for some time to come. However, what brought all the science to us is going to end. I feel sad it has to be so. However, I can look back and just feel so grateful, so lucky that I found myself in the right place so many times.

David Southwood

Chair of the UK Space Agency Steering Board

1 comment

Comment by Malcolm Smith, FBIS posted on

David: an inspiring personal (and science) story! I know John Z. and how his team went through quite a ride to get SSP ready in time for Huygens. I also recall the disappointment of Beagle2's loss. Originally I was to have studied for an MSc. at Canterbury under John, looking at places on Mars suitable for Beagle2 (and Kent's Mars weather sensors) in 1999/2000. For various reasons this changed to Mercury and then the BepiColombo lander, via the OU. A few years later I found myself having to pull away from space science studies and the OU. The dream of a future space career is still 'out there' for me, but as John Lennon said "Life is what happens whilst you were making other plans". - Malcolm Smith