The latest of the Open University’s excellent 60 Second Adventures in Microgravity tackles research using bed rest.

One challenge in medical research is getting a large enough group of people to study that you can be satisfied your results are reliable, and not just an indication of natural variation or coincidence. This is even more true in space, as the number of astronauts is very limited, and their time is precious. So, researchers use subjects in bed rest facilities on the ground. This may seem counterintuitive, and unlike many of the facilities we use for microgravity research, bed rest does not actually create freefall/weightless conditions. Rather, being confined to bed, with a slight tilt down towards the head, mimics many of the effects on the body of being in space – such as increased bone and muscle loss; lengthening of the spine; redistribution of fluids towards the top of the body.

Through our membership of the European Space Agency, British researchers use special facilities in France and Germany where around 20 healthy volunteers at a time take part in campaigns of up to 60 days. They are literally just resting in bed – which is not as attractive as it might initially sound when you consider that they must do everything in bed: washing, eating, using the toilet and so on.

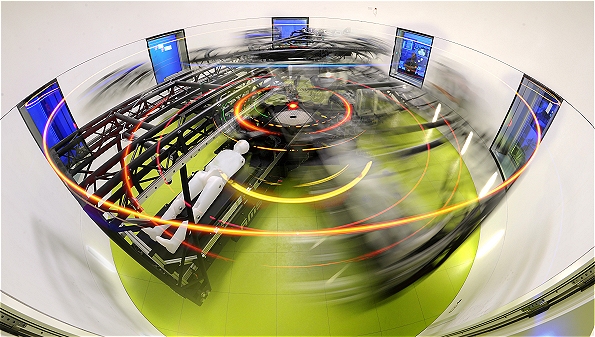

Studying the effects, and ways to lessen their impact, is crucial to enabling longer stays in space – something that will be necessary as people venture further beyond Earth. For example, whereas typical missions to the International Space Station are just 6 months long, the first human missions to Mars are likely to take at least 21 months (9 months travel each way, and 3 months on, or orbiting, Mars). Recent ESA campaigns have looked at how effective different types of exercise and nutrition are at counteracting the physical deconditioning, and early next year a series of experiments using ‘artificial gravity’ will commence. (This may sound wonderfully sci-fi, but essentially it means being spun round in a big centrifuge a few times a day.)

Of course, although this work will help future space missions, but you may legitimately be asking ‘why should I care about supporting the one-in-sixty-million of us who actually spends any time in space?’ One answer is that the adverse effects of bed rest – and for that matter, of being in space – are in many ways similar to some of the problems associated with ageing. In an ageing society, the challenge of lifelong health, and improving the wellbeing of the elderly, has become more pressing than ever. Through understanding the biological mechanisms which control things such as bone and muscle loss, we can help people to live healthier, happier lives.

Similarly, chronic conditions are often accompanied by these same symptoms; research using healthy subjects in tightly controlled conditions therefore gives valuable information on the biological processes at work, leading to better treatment and recovery.

Leave a comment