We’re lucky at the moment to have a comet visiting the inner Solar System that’s bright enough to see with a pair of binoculars, and it may in the coming week or so just reach naked-eye visibility.

Comet Lemmon, or C/2025 A6 (Lemmon), was discovered by astronomers at the Mount Lemmon Survey, in Arizona, in January. This comet spends most of its time in the very distant outer Solar System, far beyond the orbit of the ice giant planet Neptune.

Comets are icy, dusty objects and as they come closer to the Sun in their orbits, the warmth of our star causes the ices on their surface to go from a solid to a gaseous state.

Dust particles and gas are released in this process and the comet appears to brighten in the night sky. The dust particles scatter sunlight and as they are left in space, and swept back by the solar wind from our star, they form beautiful, seemingly glowing, tails. That’s what’s happened with Comet Lemmon in recent weeks and now its tail and a glowing cloud of gas, known as the ‘coma’, around the main body of the comet have become bright enough to be visible in a good pair of binoculars.

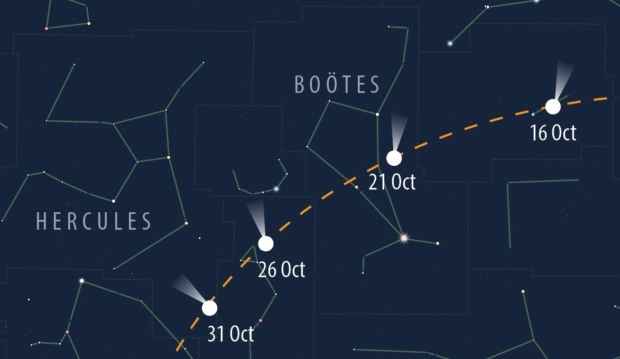

The comet is currently low in the northwestern sky after nightfall (around 8:00 pm UK time would be a good time to look this week), in the constellation of Boötes, not far from the bright star Arcturus, but in the coming days it will move into the constellation Serpens.

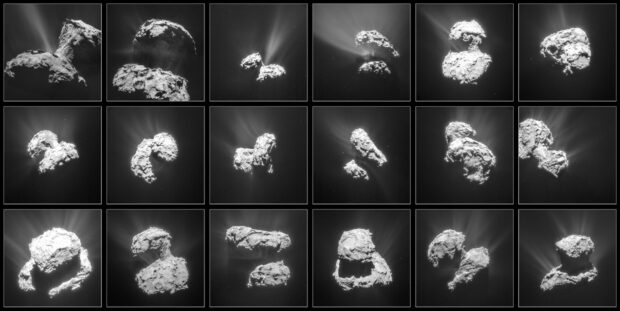

Comets are ancient objects made of primordial materials leftover from the formation of the Solar System; studying them therefore allows scientists to piece together the history and the origins of planets like Earth.

The UK is deeply involved in all kinds of cometary science including space missions to understand these icy visitors. Along with our international partners, UK industry and academia was involved in the pioneering European Space Agency Rosetta mission which visited and studied up-close the icy body, or ‘nucleus’, of the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

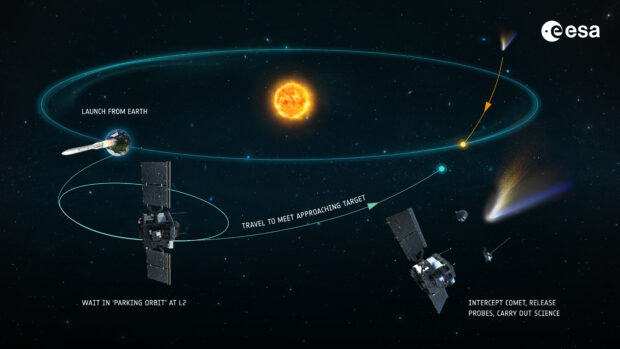

In the future the UK will also play a key part in the ESA Comet Interceptor mission. It’s aiming for launch in mid-2028 to mid-2029 and, once in space, will sit waiting for a suitable cometary target to visit and study in detail. UK researchers are involved in the Comet Interceptor mission science, including the selection of the spacecraft’s destination. One of the science instruments onboard, which will examine the composition of the comet, is also being developed and led by the University of Oxford while another, a magnetometer, is being led by Imperial College London.

Leave a comment