The longer nights of October provide more time to see the autumnal skies before the nights get chiller!

It’s a great month for meteors, seeing the closest and brightest galaxy in our skies, and later in the month there’s a chance to see a comet without the need for binoculars or a telescope.

October’s night sky sights

Saturn is still prominent in the south-eastern skies after dark (you can use last month’s sky map to find it), and the ringed planet will appear very close to our Moon on the night of 14 October while the Moon is around 90% illuminated.

Jupiter is visible low in the north-east soon after dark, lying just to the left of red-giant star Aldebaran in the constellation of Taurus, and chasing the small cluster of stars known as the Pleiades across the sky.

The stars of the Pleiades are relatively young in cosmic terms, likely appearing in our night sky around 100 million years ago. As they travel around our galaxy they are currently passing through a massive cloud of interstellar gas.

Larger telescopes or long exposure photography reveal that the stars are illuminating this nebula just as a torch illuminates the mist of a foggy night.

The Andromeda Galaxy is the closest large galaxy to our own, and is believed to host around a trillion stars.

It actually spans the width of around six full moons in our night sky, but only the brighter, star-dense core of Andromeda is visible to the naked eye.

The constellations of Cassiopeia, Perseus and Auriga are visible within the star-rich band of our Milky Way Galaxy, rising in the east after dark this month. They’re visible in the photo above, and you can use the star map below to find them.

The constellation of Ursa Major (the Great Bear) appears to walk across the northern horizon through the nights of this month.

The brighter stars that make up the bear’s back and tail are brighter than the others in this constellation, and the pattern they form has become known as the Plough, or Big Dipper.

Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) appears to have survived its close passage around the Sun and has been spotted with the naked eye late last month.

Heading back to the outer edges of our Solar System, the comet will pass by Earth on 14 October at a distance of 71 million km or 44 million miles.

By 16 – 20 October, the comet should be visible just to the left of the bright star Arcturus, the red-giant star that lies low in the western sky as darkness falls.

October’s meteor showers

The Draconids meteor shower peaks around 8-9 October and will see fragments of rock, ice and dust from Comet Giacobini-Zinner entering our atmosphere.

Even though the fragments from this comet are among the slower meteors to streak across our sky, they’re still travelling at 21 kilometres (13 miles) per second!

By contrast, the fragments from Halley’s Comet that make up the Orionids meteor shower later in the month will enter our atmosphere at around 66 kilometres (40 miles) per second. This meteor shower is active all month and peaks around 21-22 October.

Towards the end of October we’ll also start to see meteors from the Taurid meteor shower that peaks next month, so it’s a great month to wrap up warm, head outside and spend some time looking up!

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Did you know?

Halley’s Comet last passed through our inner Solar System in 1986, and its debris trail is responsible for both this month’s Orionids meteor shower and the Eta Aquariids meteor shower that we see each May.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Space science and exploration

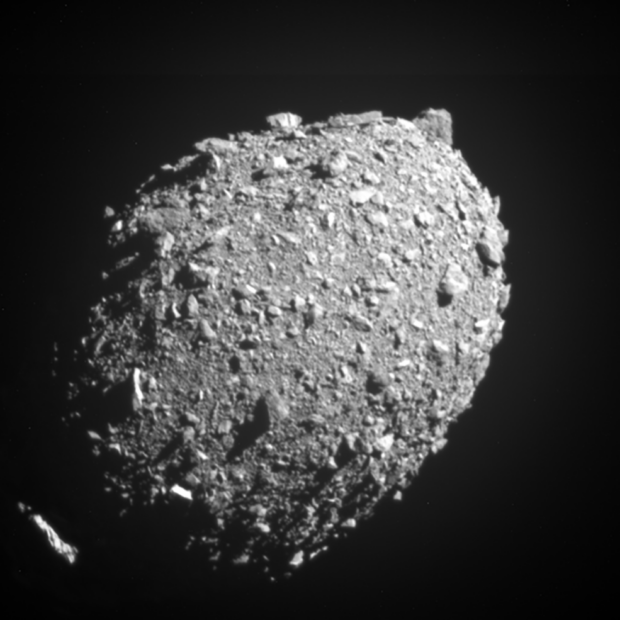

The European Space Agency will launch their ‘HERA’ mission this month to study the asteroid Dimorphos.

If that name seems familiar, it’s because NASA’s ‘DART’ (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) spacecraft smashed into it (intentionally!) around two years ago, to test whether ‘kinetic impact’ was a viable approach to deflecting Earth-bound asteroids in the future.

ESA’s HERA mission will inspect the asteroid and the crater left by DART to learn more about the composition of near-Earth asteroids and the most effective approaches to reaching, studying, and, should the time come, deflecting such objects in the future.

HERA successfully launched on 7 October - you can find more information about the HERA mission here.

NASA also plan to launch their ‘Europa Clipper’ mission this month to study Europa, Jupiter’s fourth largest moon.

The mission will get as close as 25km (16 miles) to Europa’s surface after its arrival in 2030, studying the moon’s icy shell and seeking to understand the nature of the oceans that lie beneath it.

Scientists believe that beneath the thick icy crust, Europa’s oceans may be 60 - 150km (40 – 100 miles) deep. With the icy moon’s core being heated by its interactions with Jupiter and its larger moons Ganymede, Callisto and Io, Europa’s oceans are fascinating place to search for life outside of our planet.

Leave a comment