Why Earth Observation?

It's not every day I attend a workshop where satellites, bananas, livestock, and ethics are central to the conversation.

What links these seemingly unrelated themes is data – powerful data which includes valuable information from Earth observation satellites that helps people to adapt to, and mitigate, the devastating effects of climate change around the world.

Over the past month or so our planet has experienced a multitude of extreme weather events, including the worst floods for sixty years in South Sudan, deadly tornadoes ripping across US states, Micronesian states suffering significant coastal flooding, and a super-typhoon slamming into the Philippines.

It is therefore imperative that we work across borders to forge trusted partnerships, learn lessons from each other, and maximise utilisation of technology and data to drive climate action while always being cognisant of ethical issues which might counteract best intentions.

Collaboration

This was the focus of a virtual COP26 event called ‘In Space We Trust’, hosted by the UK Knowledge Transfer Network and which I co-organised with the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data and Space4Climate group.

As part of a small team delivering the UK Space Agency’s International Partnership Programme (IPP) which has grant-funded 43 projects in collaboration with 47 countries since 2016 to develop space solutions to tackle global challenges, I was delighted to moderate a virtual fireside chat in which a diverse group of IPP international partners and data ethicists discussed how satellite data is helping to improve food security and humanitarian support in ongoing initiatives, and how to integrate geospatial data in decision-making.

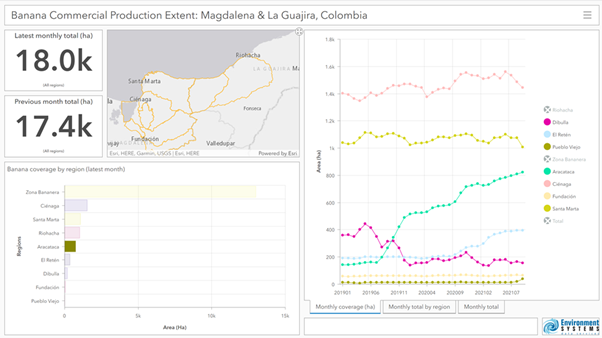

Personal perspectives of IPP international representatives started with the Executive President of ASBAMA, a Colombian banana growers’ federation and partner of the ‘EO4cultivar’ project.

He highlighted how they have been provided with data to help monitor banana production in near-real time, leading to better decision making and therefore improved sustainability.

Then the Director of Mongolia’s Centre for Nomadic Pastoralism Studies, who is involved in the ‘SIBELIUs’ project, revealed that while having access to maps which show the geographical location of good pastureland (i.e. not impacted by extreme weather events called ‘dzuds’) is hugely valuable, this can also cause conflict among interested local herders who lack standards and accreditation to effectively manage the area and/or technical capacity to use the information.

Trust

The theme running through both these accounts is trust: trust in the space-based information being provided—be that a map, weather data, mobile app informing farmers when to water their crops or where to take action to address poor crop health—trust in the people providing it, and trust that the information can work effectively with existing policies and procedures.

This was explored by representatives of the International Research Institute for Climate & Society at Columbia University in the US who talked about the importance of ensuring that all voices are heard, and constraints and opportunities therefore understood, to be able to deliver trusted, sustainable space solutions.

These different perspectives exemplified the variety of considerations required to successfully deliver space solutions for climate action.

While forging and nurturing trusted partnerships between stakeholders is obviously crucial, what really struck me during the conversations is the need for inherent flexibility in every programme and project to ensure that changing requirements—for political, economic, cultural, operational or environmental reasons—can be adjusted along the way.

I was also struck by the respect for the differences amongst us all as human beings living in countries facing an array of climate challenges that can be experienced and managed in so many different ways.

This is, of course, a familiar message, and one heard in numerous discussions at COP26 and elsewhere. But it is a message which must continue to be recognised and practiced if we are to get better at integrating space technology and data into global climate action policies.

Liz Cox

Head of International Engagement – International Partnership Programme

UK Space Agency

Leave a comment